What's Inside a Style?

If all you want to do is use a style or create a new one with a few tweaks, you now know everything you need. If, however, you want to make more substantial changes, things start to get "interesting."

Elements

While each style controls a single type of widget, each widget is usually composed of smaller pieces, called elements. It's the job of the style author to construct the entire widget out of these smaller elements. What these elements are depends on the widget.

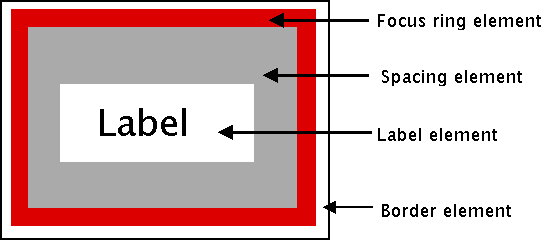

Here's an example of a button. It might have a border on the very outside. That's one element. Just inside that, there may be a focus ring. Normally, it's just the background color, but could be highlighted when a user tabs into the button. So that's a second element. Then there might be some spacing between that focus ring and the button's label. That spacing is a third element. Finally, the text label of the button itself is a forth element.

|

|---|

| Possible elements of a button. |

Why might the style author have divided it up that way? If you have one part of the widget that may be in a different location or a different color than another, it may be a good candidate for an element. Note that this is just one example of how a button could be constructed from elements. Different styles and themes could (and do) accomplish this in different ways.

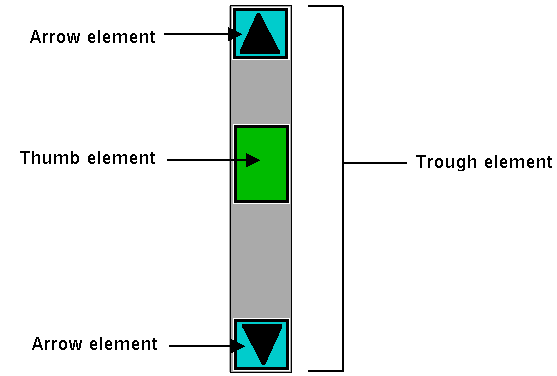

Here is an example of a vertical scrollbar. It consists of a "trough" element, which contains other elements. These include the up and down arrow elements at either end and a "thumb" element in the middle (it might have additional elements, like borders).

|

|---|

| Possible elements of a scrollbar. |

Layout

Besides specifying which elements make up a widget, a style also defines how those elements are arranged within the widget. This is called their layout. Our button had a label element inside a spacing element, inside a focus ring element, inside a border element. Its logical layout is this:

border {

focus {

spacing {

label

}

}

}

We can ask Tk for the layout of the TButton style:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { println!( "{}", tbutton_style.layout()? ); // "Button.border -sticky nswe -border 1 -children {Button.focus -sticky nswe -children {Button.spacing -sticky nswe -children {Button.label -sticky nswe}}}" }

If we clean this up and format it a bit, we get something with this structure:

Button.border -sticky nswe -border 1 -children {

Button.focus -sticky nswe -children {

Button.spacing -sticky nswe -children {

Button.label -sticky nswe

}

}

}

This starts to make sense; we have four elements, named Button.border,

Button.focus, Button.spacing, and Button.label. Each has different element

options, such as children, sticky, and border that specify layout or

sizes. Without getting into too much detail at this point, we can clearly see

the nested layout based on the children and sticky attributes.

Styles uses a simplified version of Tk's

packgeometry manager to specify element layout. This is detailed in the style reference manual page.

Element Options

Each of these elements has several different options. For example, a label element has a font and a foreground color. An element representing the thumb of a scrollbar may have one option to set its background color and another to provide the width of a border. These can be customized to adjust how the elements within the overall widget look.

You can determine what options are available for each element? Here's an example

of checking what options are available for the label inside the button (which we

know from the layout method is identified as Button.label):

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let options = tk .element("Button.label") .element_options()? .iter() .fold( String::new(), |acc,opt| format!( "{} {}", acc, opt )); println!( "{}", options ); // " -compound -space -text -font -foreground -underline -width -anchor -justify -wraplength -embossed -image -stipple -background" }

In the following sections, we'll look at the not-entirely-straightforward way to work with element options.